There have been a vast number of reports, based chiefly on clinical evidence alone, purporting to show that oral foci of infection either cause or aggravate a great many systemic diseases. The diseases most frequently mentioned are:

Arthritis, chiefly of the rheumatoid and

rheumatic fever type.

Valvular heart disease, particularly subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Gastrointestinal diseases..

Ocular diseases.

Skin diseases.

Renal diseases.

Arthritis of the rheumatoid type is a disease of unknown etiology, but probably represents only one manifestation of a generalized systemic disease. It bears close resemblance to many features of rheumatic fever, and though microorganisms cannot be cultured from the joints, the patients frequently have a high antibody titer to group A hemolytic streptococci. This suggests a tissue hypersensitivity reaction as the cause for the basic inflammatory reactions.

It was only logical that dental infection would be implicated because of the occurrence of streptococcal infection in the mouth. The Ninth Rheumatism Review (Hench) emphasized several points in favor of the septic foci theory of the eti- ology of rheumatoid arthritis. These include the following:

1. Streptococcal infections of the throat, tonsils, or nasal sinuses may precede the initial or recurrent attacks.

2. Removal of a septic focus show dramatic improvement sometimes.

3. The pathologic and anatomic features of lymphoid tissue in tonsillar infection, sinus infection, and root abscesses suggest that toxic products can be absorbed into the circulation.

4. A temporary bacteremia may occur immediately after tonsillectomy or tooth extraction or after vigorous massage of the gums.

The following points, however, are against this theory:

1. Often no infectious focus can be found.

2. No dramatic results are produced when a focus has been extirpated.

3. Many persons who are in good health or are suffering from a disease other than rheumatoid arthritis may have septic foci in the same situations and of the same magnitude as patients who are suffering from rheumatoid arthritis.

4. Sulfonamides, antibiotics, and vaccines fail to produce beneficial effects.

The failure of removal of oral foci to result in improvement of rheumatoid arthritis has proved the wisdom of the advice of Freyberg, who stated that two conditions should govern the manage- ment of foci of infection:

Just like when a patient without rheumatic disease should have abscessed teeth or infected tonsils removed, so should the patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

By removal of such infected tissues, the patient’s general health might be improved, and thereby his ability to combat the arthritis might be indirectly facilitated.

He stressed that the patient should be warned that removal of such foci might not be of direct value as treatment for his arthritic disease.

Subacute bacterial endocarditis (or ‘infective endocarditis’) can without doubt be related to oral infection, since

There is a close similarity in most instances between the etiologic agent of the disease and the microorganisms in the oral cavity, in the dental pulp, and in periapical lesions.

Symptoms of subacute bacterial endocarditis have been observed in some instances shortly after extraction of teeth.

Transient bacteremia frequently follows tooth extraction.

This disease is generally recognized as being due to the accretion of bacterial vegetation on heart valves that are predisposed to the develop- ment of the condition, usually by rheumatic fever or congenital heart disease. Although streptococci of the viridans type once caused the majority of the subacute cases of bacterial endocarditis, the advent of the antibiotics has resulted in the drug-resistant microorganisms assuming a more important role.

Numerous studies have already been cited indicating that tooth extraction is often followed by a streptococcal bacteremia of the type usually associated with subacute bacterial endocarditis. In addition, many reports have indicated that the appearance of this form of endocarditis is sometimes preceded by tooth extraction. Elliott, for example, reported that 13 of 56 patients, or 23 percent, gave a history of recent dental operations preceding the occurrence of infective endocarditis. Geiger noted that the beginning of subacute bacterial endocarditis among 50 patients was specifically related to tooth extraction in 12 cases. Bay reported that in a series of 26 cases of subacute bacterial endocarditis, six patients had had dental extraction, while Barnfield reported six of 92 cases to be associated with tooth extraction. In a series of 250 cases reported by Kelson and White, the predisposing cause in one of each four cases of bacterial endocarditis was found to be some dental procedure, usually tooth extraction.

The majority of cases of subacute bacterial endocarditis reported in the literature as following tooth extraction have occurred within a few weeks to a few months after the dental procedure. Pre- medication of patients with various antibiotics is usually prescribed to prevent the transient bacteremias that follow dental manipulations, and this prophylactic measure is considered to be an absolute necessity in patients who have a past history of rheumatic fever or other evidence of known valvular damage. In contrast, BL Strom, and his associates noted in their study of patients with endocarditis who either did or did not have dental treatment at a reasonable interval before the onset of the disease concluded that there was no relationship between dental treatment and bacterial endocarditis (although the study did demonstrate a strong relation between cardiac valve pathology and endocarditis). Studies by van der Meer JT. Thompson J. and associates (1992) and B Hoen. Lacassin, F. and associates (1995) have also supported a very low risk rate for endocarditis with dental treatment. The most recent American Heart Association guidelines for the prevention of endocarditis clearly state that the vast majority of endocarditis due to oral organisms is not related to dental treatment procedures.

Gastrointestinal diseases have been periodically related to oral foci of infection. Gastric and duo- denal ulcers have reportedly been produced exper- imentally by the injection of streptococci. Some workers have proposed that the constant swallowing of microorganisms might lead to a variety of gastrointestinal diseases. In most instances, however, the low pH of the gastric secretions is an adequate defense against such infection.

The lack of either clinical or experimental evidence of a relation between oral foci of infection and gastrointestinal diseases suggests that such a relation is highly questionable.

Ocular diseases have often been attributed in the ophthalmologic literature to primary foci of infection such as those associated with the teeth, tonsils, sinuses, genitourinary tract, and so forth. Guyton and Woods carried out a study on 562 patients hospitalized with iritis, cyclitis, choroiditis, and generalized uveitis. Definite evidence of foci of infection as the etiologic factor was found in 31, or 5.5 per cent of the patients, and presump- tive evidence of the same etiologic factor in 116, or 20.6 per cent of the patients. But when this group of patients was compared with a control group of 517 persons without uveitis, the percentages of foci of infection were almost identical. This would indicate that the role of foci of infection in this situation is questionable at the very least.

Woods evaluated the role of foci of infection in ocular disease, and as pointed out by Easlick, listed the factors supporting the hypothesis as follows:

1. Many ocular diseases occur in which no systemic cause other than the presence of remote foci of infection can be demonstrated.

2. Numerous instances of prompt and dra- matic healing of ocular diseases are reported to have followed the removal of these foci.

3. Sudden transient exacerbations occasionally are observed after the removal of teeth or tonsils and often are accepted as an indication of a relationship.

4. Some reports indicate the presence of blood stream infection in the early stages of ocular disease.

5. Iritis may be produced in animal experiments by the intravenous injection of microorganisms, especially streptococci.

6. Very little evidence is to support that some microorganisms may have a special predilection for ocular tissue.

There are objections to these points, however, and they may be listed as follows:

1. Many, otherwise healthy people, can be found to have focal infection, but no ocular disease.

2. Spontaneous cures frequently occur if nothing is done.

3. The exacerbations following surgery may also be explained as simple examples of the Shwartzman phenomenon, the flar- ing of an inflammatory focus through absorption of nonspecific protein, or on the basis of allergic shock to specifically sensitized tissue.

4. Positive blood cultures and cultures of the aqueous humor are rare in cases of acute iritis, and few secondary infections of the uveal tract follow the common transient streptococcal or staphylococcal bac- teremias in patients.

5. Although lesions do occur in the eyes of laboratory animals after intravenous injection of microorganisms, they also occur with equal frequency in other organs, and the eye lesions are usually purulent, only occasionally simulating the clinical lesions of the iris and uveal tract.

6. Scientific proof that ocular disease of unclear etiology may be caused by bacte- ria from remote foci of infection appears to be missing, and the acceptance of the conclusion must be based largely on faith; however, there exists a strong possibility (on research, not clinical basis) that sensi- tization to secondary metastatic products from a focus may be related to ocular disease.

Studies with ACTH and Cortisone in ocular disease suggest that, in many such cases, the oph- thalmologist may be dealing with an abnormal metabolism rather than with a reaction to a focus of infection. Scientific evidence establishing dental foci of infection as the etiologic agent in oph- thalmic disease is scanty. If such a relationship does exist, the most probable mechanism is sensitization.

Skin diseases have been suggested by some dermatologists to be related to foci of infection in occasional instances. Fox and Shields discussed dermatologic lesions and stated that the 10 most common skin diseases are:

(1) acne.

(2) seborrheic dermatitis,

(3) tinea (fungus infection of the scalp. body, groin, hands, feet, nails),

(4) eczema (eczematous dermatitis, nummular eczema, infec- tious eczematoid dermatitis, and atopic dermati- tis),

(5) dermatitis venenata (eczematous contact type dermatitis, occupational dermatitis),

(6) impetigo,

(7) scabies,

(8) urticaria,

(9) psoriasis, and

(10) pityriasis rosea.

Of these diseases, only some forms of eczema and possibly urticaria can conceivably be related to oral foci of infection.

A few other dermatoses have been related to focus of infection, although there is little scientific proof of this association. These diseases include erythema multiforme, pustular dermatitis, lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, and pustular acrodermatitis. If such a relationship does exist, the mechanism is probably sensitization rather than metastatic spread of microorganisms.

Renal diseases of certain types are sometimes attributed to foci of infection. The type of microorganism most commonly involved in urinary infections is Escherichia coli, although other staphylococci and streptococci also may be cul- tured. Of the streptococci, Streptococcus hemolyticus seems to be most common. This streptococcus is an uncommon inhabitant of dental root canals or periapical and gingival areas. Since the microor- ganisms commonly involved in oral infection are only infrequently involved in renal infections, it appears that there is little relation between the two and that oral foci of infection play a small role even when the possibility of superimposition on a dam- aged urinary tract exists.

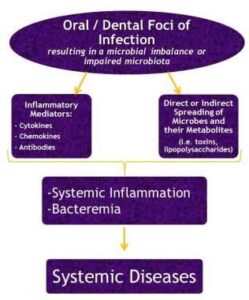

The present evidence for the relationship of oral microorganisms and systemic disease, particularly that involving the coronary arteries, is very limited. Occurrence of metastatic infections from the mouth to distant bodily sites is also not very common.