Aggressive periodontitis generally affects systemically healthy individuals less than 30 years old, although patients may be older.

Aggressive periodontitis may be universally distinguished from chronic periodontitis by the age of onset, the rapid rate of disease progression, the nature and composition of the associated subgingival microflora, alterations in the host’s immune response, and a familial aggregation of diseased individuals. In addition, a strong racial influence is observed in the United States; the disease is more prevalent among African Americans.

Aggressive periodontitis describes three of the diseases formerly classified as “early-onset periodontitis.” Localized aggressive periodontitis was formerly classified as “localized juvenile periodontitis” (LJP). Generalized aggressive peri- odontitis encompasses the diseases previously classified as “generalized juvenile periodontitis” (GJP) and “rapidly progressive periodontitis” (RPP).

LOCALIZED AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS

Clinical Characteristics :

Localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP) usually has an age of onset at about puberty. Clinically, it is charac- terized as having “localized first molar/incisor presenta- tion with interproximal attachment loss on at least two permanent teeth, one of which is a first molar, and involving no more than two teeth other than first molars and incisors . The localized distribution of lesions in LAP is characteristic but as yet unexplained. The following possible reasons for the limitation of periodontal destruction to certain teeth have been suggested:

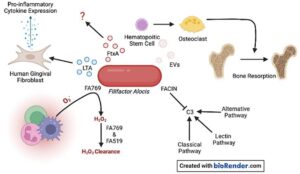

1. After initial colonization of the first permanent teeth to erupt (the first molars and incisors), Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans evades the host defenses by different mechanisms, including production of polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) chemotaxis- inhibiting factors, endotoxin, collagenases, leukotoxin, and other factors that allow the bacteria to colonize the pocket and initiate the destruction of the periodontal tissues. After this initial attack, adequate immune defenses are stimulated to produce opsonic antibodies to enhance the clearance and phagocytosis of invading bacteria and neutralize leukotoxic activity. In this manner, colonization of other sites may be prevented. A strong antibody response to infecting agents is one characteristic of LAP

2. Bacteria antagonistic to A. actinomycetemcomitans may colonize the periodontal tissues and inhibit A. actinomycetemcomitans from further colonization of periodontal sites in the mouth. This would localize A. actinomycetemcomitans infection and tissue destruction.

3. A. actinomycetemcomitans may lose its leukotoxin- producing ability for unknown reasons.” If this happens, the progression of the disease may become arrested or impaired, and colonization of new periodontal sites may be averted.

4. A defect in cementum formation may be responsible for the localization of the lesions. Root surfaces of teeth extracted from patients with LAP have been found to have hypoplastic or aplastic cementum. This was true not only of root surfaces exposed to periodontal pockets, but also of roots still surrounded by their periodontium.

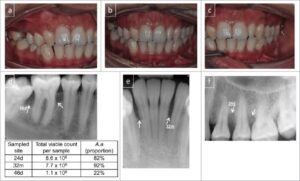

A striking feature of LAP is the lack of clinical inflam- mation despite the presence of deep periodontal pockets and advanced bone loss . Furthermore, in many cases the amount of plaque on the affected teeth is minimal, which seems inconsistent with the amount of periodontal destruction present. The plaque that is present forms a thin biofilm on the teeth and rarely mineralizes to form calculus. Although the quantity of plaque may be limited, it often contains elevated levels of A. actinomycetemcomitans, and in some patients, Porphyromonas gingivalis. The potential significance of the qualitative composition of the microbial flora in LAP is discussed later in the section on risk factors.

As the name suggests, localized aggressive periodon- titis progresses rapidly. Evidence suggests that the rate of bone loss is about three to four times faster than in chronic periodontitis. Other clinical features of LAP may include

(1) distolabial migration of the maxillary incisors with concomitant diastema formation,

(2) increasing mobility of the maxillary and mandibular incisors and first molars,

(3) sensitivity of denuded root surfaces to thermal and tactile stimuli, and (4) deep, dull, radiating pain during mastication, probably caused by irritation of the supporting structures by mobile teeth and impacted food. Periodontal abscesses may form at this stage, and regional lymph node enlargement may occur.

Not all cases of LAP progress to the degree just de- scribed. In some patients the progression of attachment loss and bone loss may be self-arresting.

Radiographic Findings :

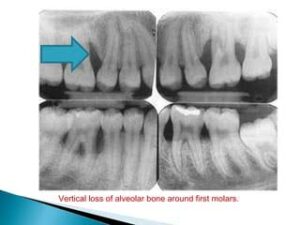

Vertical loss of alveolar bone around the first molars and incisors,

beginning around puberty in otherwise healthy teenagers, is a classic diagnostic sign of LAP. Radiographic findings may include an “arc-shaped loss of alveolar bone extending from the distal surface of the second premolar to the mesial surface of the second molar”. Bone defects are usually wider than usually seen with chronic periodontitis .

Prevalence and Distribution by Age and Gender :

The prevalence of LAP in geographically diverse adoles- cent populations is estimated at less than 1%. Most reports suggest a low prevalence, about 0.2%. Two inde- pendent radiographic studies of 16-year-old adolescents, one in Finland” and the other in Switzerland, followed the strict diagnostic criteria delineated by Baer and reported a prevalence rate of 0.1%. A clinical and radio- graphic study of 7266 English adolescents 15 to 19 years old also showed a prevalence rate of 0.1%. In the United States a national survey of adolescents age 14 to 17 reported that 0.53% had LAP. Blacks were at much higher risk for LAP, and black male teenagers were 2.9 times more likely to have the disease than black female adolescents. In contrast, white female teenagers were more likely to have LAP than white male adolescents. Several other studies have found the highest prevalence of LAP among black males, 40 followed in descending order by black females, white females, and white males.

Localized aggressive periodontitis affects both males and females and is seen most frequently in the period between puberty and 20 years of age. Some studies have suggested a predilection for female patients, particularly in the youngest age groups, whereas others report no 20 male-female differences in incidence when studies are de- signed to correct for ascertainment bias.

GENERALIZED AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS :

Clinical Characteristics

Generalized aggressive periodontitis (GAP) usually affects individuals under age 30, but older patients also may be affected. In contrast to LAP, evidence suggests that individuals affected with GAP produce a poor antibody response to the pathogens present. Clinically. GAP is characterized by “generalized interproximal attachment loss affecting at least three permanent teeth other than first molars and incisors.” The destruction appears to occur episodically, with periods of advanced destruction followed by stages of quiescence of variable length (weeks to months or years). Radiographs often show bone loss that has progressed since the radiographic examination.

As seen in LAP, patients with GAP often have small amounts of bacterial plaque associated with the affected teeth, Quantitatively, the amount of plaque seems inconsistent with the amount of periodontal destruction. Qualitatively, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and Tanneretta forsythia (formerly Bacteroides forsythus) frequently are detected in the plaque that is present.

Two gingival tissue responses can be found in cases of GAP. One is a severe, acutely inflamed tissue, often proliferating, ulcerated, and fiery red. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or with slight stimulation. Suppuration may be an important feature. This tissue response is believed to occur in the destructive stage, in which attachment and bone are actively lost. In other cases the gingival tissues may appear pink, free of inflammation, and occasionally with some degree of stippling, although stippling may be absent . However, despite the apparently mild clinical appearance, deep pockets can be demonstrated by probing. Page and Schroeder believe that this tissue response coincides with periods of quiescence in which the bone level remains stationary. Some patients with GAP may have systemic manifesta- tions, such as weight loss, mental depression, and general malaise.

Patients with a presumptive diagnosis of GAP must have their medical histories updated and reviewed. These patients should receive medical evaluations to rule out possible systemic involvement. As seen with LAP, cases of GAP may be arrested spontaneously or after therapy, whereas others may continue to progress inexorably to tooth loss despite intervention with conventional treatment.

Radiographic Findings :

The radiographic picture in generalized aggressive peri- odontitis can range from severe bone loss associated with the minimal number of teeth, as described previously, to advanced bone loss affecting the majority of teeth in the dentition . A comparison of radiographs taken at different times illustrates the aggressive nature of this disease. Page et al.” described sites in GAP patients that demonstrated osseous destruction of 25% to 60% during a 9-week period. Despite this extreme loss, other sites in the same patient showed no bone loss.

Prevalence and Distribution by Age and Gender :

In a study of untreated periodontal disease conducted in Sri Lanka by Löe et al., 8% of the population had rapid progression of periodontal disease, characterized by a yearly loss of attachment of 0.1 to 1.0 mm. A U.S. national survey of adolescents age 14 to 17 reported that 0.13% had GAP. In addition, blacks were at much higher risk than whites for all forms of aggressive periodontitis, and male teenagers were more likely to have GAP than female adolescents .

RISK FACTORS FOR AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS :

Microbiologic Factors

Although several specific microorganisms frequently are detected in patients with localized aggressive periodon- titis (A.actinomycetemcomitans, Capnocytophaga spp… Eikenella corrodens, Prevotella intermedia, and Campylobacter rectus), A. actinomycetemcomitans has been implicated as the primary pathogen associated with LAP. As summa- rized by Tonetti and Mombelli,” this link is based on the following evidence:

1. A. actinomycetemcomitans is found in high frequency (approximately 90%) in lesions characteristic of LAP.

2. Sites with evidence of disease progression often show elevated levels of A. actinomycetemcomitans.

3. Many patients with the clinical manifestations of LAP have significantly elevated serum antibody titers to A. actinomycetemcomitans.

4. Clinical studies show a correlation between reduction in the subgingival load of A. actinomycetemcomitans during treatment and a successful clinical response.

5. A. actinomycetemcomitans produces a number of virulence factors that may contribute to the disease process.

Not all reports support the association of A. actino- mycetemcomitans and localized aggressive periodontitis. In some studies, A. actinomycetemcomitans either could not be detected in patients with this form of disease or could not be detected at the previously reported frequencies. Another study found elevated levels of P gingivalis, P. intermedia, Fusobacterium nucleatum, C. rectus, and Treponema denticola in patients with either localized or generalized aggressive disease, but no significant asso- ciation was found between the presence of aggressive disease and A. actinomycetemcomitans. In addition, A. actinomycetemcomitans often can be detected in peri- odontally healthy subjects, suggesting that this micro-organism may be part of the normal flora in many individuals .

Electron microscopy studies of LAP have revealed bacterial invasion of connective tissue that reaches the bone surface. The invading flora has been described as morphologically mixed but composed mainly of gram- negative bacteria, including cocci, rods, filaments, and spirochetes.” Using different methods, including immuno- cytochemistry, several tissue-invading microorganisms have been identified as A. actinomycetemcomitans, Capnocytophaga sputigena, Mycoplasma species, and spirochetes.