- ODONTOGENIC CARCINOMAS

METASTASIZING AMELOBLASTOMA

Traditionally, ameloblastoma has been regarded as a benign tumor that can be locally aggressive but occasionally can metastasize and kill the patient. The prospect that all ameloblastomas could represent lowgrade malignant neoplasms deserves consideration. The term ‘metastasizing ameloblastoma’ is used to describe a tumor that shows histologic features of classic ameloblastoma in the gingiva or jaw and has metastatic deposits elsewhere.

Clinical Features :-

Typically, the primary ameloblastoma arises in the mandible of a young adult. The average age at presentation is 30 years, but 33 per cent of patients are younger than 20 years of age. After a mean interval of approximately 11 years, metastatic nodules develop in the lung (80 per cent), cervical lymph nodes (15 per cent), or extragnathic bones. Typically, the pulmonary metastases are multifocal and involve both lungs. The median survival after discovery of the metastatic lesion is about two years. Innocuous lung ‘granulomas’ that are seen on routine chest films of a patient who has ameloblastoma can prove to be silent metastases. Kunze et al. (1985) noted that most patients had multiple recurrences of the jaw ameloblastoma. The multiple recurrences could result from an intrinsically more aggressive tumor or from surgery-associated tumor ‘spillage’ into adjacent tissue or tumor embolization into lymphatic or blood vessels. The primary ameloblas toma can become locally aggressive (with parapharyngeal and cranial base invasion) before pul- monary metastases arise.

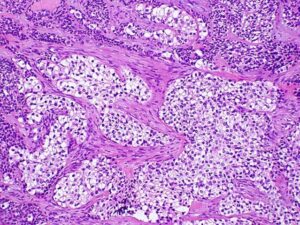

Histologic Features :-

Ameloblastoma with metastatic potential is histologically indistinguishable from conventional ameloblastoma. The metastatic ameloblastoma usually does not show any greater cytologic atypia or mitotic activity than that seen in the primary. Metastasizing ameloblastoma, ambiguously termed ‘malignant ameloblastoma’, clearly demonstrates the biologic behavior of a well-differentiated low-grade carcinoma.

Treatment :-

Metastatic ameloblastoma is managed best by surgery, but there is no evidence that it improves survival. Cervical lymph node metas- tases are managed by neck dissection. If adequate pulmonary function can be preserved, lung metastases can be excised by lobectomy. At surgery, more numerous pulmonary metastatic deposits are often identified than were apparent in diagnostic imag- ing studies. Generally, chemotherapy has been ineffective, but a short-term partial response is possible.

AMELOBLASTIC CARCINOMA

Ameloblastic carcinoma is a malignant epithelial proliferation that is associated with an ameloblastoma (carcinoma ex ameloblastoma) or histologically resembles an ameloblastoma (de novo ameloblastic carcinoma). Ameloblastic carcinoma subjectively demonstrates greater cytologic atypia and mitotic activity than ameloblastoma. Some ameloblastomas exhibit basilar hyperplasia and an increased mitotic index. These findings might warrant a designation of ‘atypical ameloblastoma’ or ‘proliferative ameloblastoma’, but they are probably insufficient to permit a diagnosis of ameloblastic carcinoma in the absence of nuclear pleomorphism, perineural invasion, or other histologic evidence of malignancy. Ameloblastic carcinoma is an aggressive neoplasm that is locally invasive and can spread to regional lymph nodes or distant sites, such as lung and bones. Usually, ameloblastic carcinoma is managed as a squamous cell carcinoma with attempted complete surgical excision, elective or therapeutic neck dissection, and postoperative radiation therapy. The prognosis is poor.

Carcinoma ex Ameloblastoma :-

A carcinoma directly contiguous with an ameloblastoma is appropriately termed a ‘carcinoma arising from an ameloblastoma’ . The carcinoma arises when an ameloblastoma undergoes ‘dedifferentiation’ (i.e. when a less-differentiated proliferative clone arises within an ameloblastoma). This aggressive clone overgrows the ameloblastoma and becomes the dominant component. A follicular or plexiform ameloblastoma blends through a narrow transition zone with a hypercellular poorly differentiated carcinoma that demonstrates sheets of disordered mitoticallyactive small basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, larger squamoid or polygonal cells with pale vesicular nuclei or elongated spindled epithelial cells. The carcinomatous cells show mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism. A low-grade spindled ameloblastic carcinoma also has been described, in which ameloblastomatous epithelium is associated with hypercellular stroma that displays elongated fibrob- lastic cells that show little cytologic atypia and scattered mitotic figures; the ‘fibroblastic cells’ display immunoreactivity for cytokeratin. Hamakawa et al., (2000) reported a squamous cell carcinoma that arose adjacent to an ameloblastoma with no apparent transition between the two components. They interpreted it as a probable ‘collision tumor’, two separate primary tumors a squamous cell carcinoma of gingival or odontogenic epithelial origin that abutted a conventional ameloblastoma.

De novo Ameloblastic Carcinoma :-

If a carcinoma lacks component of conventional ameloblastoma, its unequivocal categorization as an ameloblastic carcinoma is considerably less secure . The diagnosis of de novo ameloblastic carcinoma is based on subjective interpretation. The tumor should demonstrate vague ameloblastomatous features: a plexiform architecture that exhibits budding and anastomosing epithelial processes with peripheral palisaded cuboidal to columnar cells and central polygonal to angular cells. Tumors that lack evidence of reverse polar- ization, the so-called ‘Vickers-Gorlin’ changes that are indicative of ameloblastic differentiation, can be accepted as examples of de novo ameloblas- tic carcinoma; the stringent criterion of reverse polarity has not been required.

The possibility of a variant of squamous cell carcinoma that shows peripheral palisaded cells should be considered before a diagnosis of ameloblastic carcinoma is rendered. But the dis- tinction is of academic interest only, because squa- mous cell carcinoma and ameloblastic carcinoma are treated the same way.

Primary Intraosseous Carcinoma :-

Primary intraosseous carcinoma (PIOC) is a squamous cell carcinoma that occurs in the jaw bone. It is called ‘primary’ because it is not a secondary deposit; metastasis from a distant primary to the jaw must be excluded. It is termed ‘intraosseous’ because it develops centrally within bone; origin from sur- face stratified squamous or sinonasal epithelium must be ruled out. It lacks evidence of ameloblastic differentiation, otherwise it would be classified as a de novo ameloblastic carcinoma. If the intraosseous carcinoma demonstrates mucous cells, then a diagnosis of central mucoepidermoid carcinoma is appropriate.

Primary intraosseous carcinoma presents clinically as a diffuse enlargement of the jaw; if mucosal ulceration or mucosal tumefaction is present, the diagnosis of PIOC should be questioned. PIOC epithelium can become confluent with gingival surface stratified squamous epithelium after ero- sion of bone. Such confluence does not indicate necessarily that the carcinoma is of gingival origin if the tumor’s overall growth pattern suggests an intraosseous origin. CT images can be useful in assessing whether a putative PIOC could have originated from a gingival squamous cell carcinoma, as well as buccal and lingual cortical destruction and trismus-inducing invasion of the masticator space before involving surface oral mucosa.

PIOC is believed to arise from central odontogenic epithelium, but in rare cases, origin from incisive canal epithelium has been proposed. Cervical metastases have been identified synchronously or metachronously with a PIOC.

Solid Primary Intraosseous Carcinoma :-

Thomas et al. thoroughly reviewed the clinicoradiographic attributes of this rare tumor. The typical solid PIOC presents as a painful mass in the posterior mandible. Although the mean age at presentation is 52 years, 20 per cent of patients are younger than 34 years and 39 per cent are older than 65 years. Clinically, patients may present with pain, swelling and paresthesia.

Radiographically, 42 per cent of patients demonstrate a cup-shaped radiolucent lesion, 26 per cent demonstrate a poorly-circumscribed “moth eaten’ radiolucency, and 10 per cent exhibit a well-circumscribed radiolucency. At presentation, 31 per cent of patients have evidence of cervical metastases; however, the survival rate of patients who have regional metastases is apparently no worse than those who do not.

Most often, the tumor is treated by surgical excision and postoperative radiation therapy. Most deaths occur within two years of therapy. The overall five-year survival rate is 38 per cent.

Cystic Primary Intraosseous Carcinoma :-

Cystic PIOC (PIOC arising in an odontogenic cyst, PIOC ex odontogenic cyst) is squamous cell carcinoma that demonstrates a cystic component with a lumen that contains fluid or keratin and a lining of stratified squamous epithelium that exhibits cytologic atypia (intraepithelial neoplasia, epithelial dysplasia). If the cystic component lacks cytologic atypia, the possibilities of a gingival carcinoma that eroded bone and collided with an odontogenic cyst or of a PIOC that arose adjacent to a benign cyst might be considered.

Intraosseous carcinomas that show a cystic and a solid component can mimic an odontogenic cyst radiographically.

Squamous cell carcinoma can exhibit a predominantly cystic architecture. The theoretic possibility of a squamous cell carcinoma metastasizing to the jaw as a cystic lesion, has not been reported.

Carcinoma ex Dentigerous Cyst :-

The most common odontogenic cyst to show carcinomatous changes is the dentigerous cyst. Intraepithelial neoplasia that involves sulcular gingival epithelium can mimic carcinoma ex dentigerous cyst histologically. It typically presents as an asymptomatic or painful pericoronal radiolucent lesion that is associated with an impacted mandibular third molar. The mean age of occurrence is 59 years with male predominance. Some lesions can cause osseous destruction. Most carcinomas that arise in dentigerous cysts occur in the mandibular molar area; occasionally they are. associated with impacted canine teeth.

Histologically, the lesions demonstrate membranous connective tissue that is lined by stratified squamous epithelium that exhibits evidence of intraepithelial neoplasia (epithelial dysplasia) and is associated with an invasive well-differentiated or moderately-differentiated squamous cell carcino- ma. The lining epithelium is derived from dental follicular epithelium or gingival sulcular epitheli- um (if the tooth is partially erupted). Usually, the carcinoma is treated by surgical resection.

Carcinoma ex Odontogenic Keratocyst :’

Makowski et al. (2001) identified 15 previously reported cases of squamous cell carcinoma that arose in an odontogenic keratocyst (OKC). In most cases, radiographic findings are those of a benign OKC.

In the maxilla, OKC lining epithelium can fuse with buccal vestibular surface stratified squamous epithelium to form a chronic sinus tract that drains pus-like keratinaceous material; this ‘automarsupialized’ cyst develops thickened nonkeratinized lining epithelium that is similar to that seen in a surgically decompressed OKC. PIOC that arises in a cyst that is lined by dysplastic thickened parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium that lacks convincing features of classic OKC or orthokeratinized odontogenic cyst cannot be classified assuredly as carcinoma ex OKC.

Usually, the carcinomas have been treated by resection and postoperative radiation therapy, and infrequently with chemotherapy.

Intraosseous Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma :-

Intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma (central mucoepidermoid carcinoma, PIOC with mucous cells) arises from odontogenic epithelium or an odontogenic cyst. It represents a cystic primary intraosseous carcinoma that shows squamous differentiation and mucous cells. If a rare central mucoepidermoid carcinoma arises from ectopic salivary gland tissue that was enclaved within the mandible during development, it would be classi- fied as a primary intraosseous carcinoma. A low- grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma that presents as a retromolar mucosal mass with an underlying broad ‘cupped out’ radiolucency of the mandible may represent a conventional mucoepidermoid carcinoma derived from retromolar salivary glands that has secondarily eroded the mandible. With this presentation, a diagnosis of ‘central mucoepidermoid carcinoma’ should be questioned because central tumors do not present as mucosal masses. Some apparent maxillary intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinomas probably arise from seromucous glands that are associated with sinonasal mucosa. Most tumors are low-grade cystic lesions that grow in a broad ‘pushing’ front and demon- strate a well-circumscribed unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion. As for all neoplasms, the prognosis depends on the extent of dis- case (clinical stage) and the histologic grade of the tumor. High-grade tumors display a destructive permeative growth pattern and have metastatic potential. Typical low-grade tumors have a favorable prognosis. Death eventuates from uncontrolled local disease rather than from metastases .

Varying surgical treatments have been used, including: curettage, partial resection, en bloc resection, and hemimandibulectomy. In several cases, curettage resulted in no evidence of disease after a follow-up period of 3-19 years.