FOCAL INFECTION

Focus of infection refers to a circumscribed area of tissue, which is infected with exogenous pathogenic microorganisms and is usually located near a mucous or cutaneous surface. This should be carefully distinguished from focal infection.

The theory of focal infection played a domi- nating role in medicine for many years and has been a subject of controversy. About a century ago, William Hunter first synthesized the notion that oral microorganisms and their products were involved in a range of systemic diseases not always of obvious infectious origin, such as arthritis. Oral foci of infection have been related to general health since the very inception of the theory of focal infection early in the 20th century. This the- ory, originating during the infancy of microbiolo- gy as a science, was based chiefly upon clinical observation with little foundation in scientifically determined fact. As early as 1940, Reimann and Havens criticized the theory of focal infection with their findings. The enthusiastic acceptance of this concept by the medical and dental professions soon after its promulgation has gradually waned. But it is still of sufficient importance to warrant detailed consideration here because of its recent resurrection.

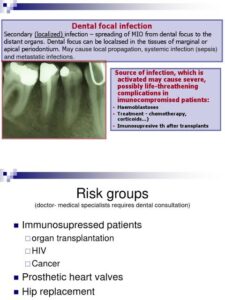

Mechanism of Focal Infection

There are two generally accepted mechanisms in the possible production of focal infection. In one instance there may be a metastasis of microorgan- isms from an infected focus by either hematoge nous or lymphogenous spread. Secondly, toxins or toxic products may be carried through the blood stream or lymphatic channels from a focus to a distant site where they may incite a hypersensitive reaction in the tissues.

The spread of microorganisms through vascu- lar or lymphatic channels is a recognized phenomenon, as is their localization in tissues. Thus cer- tain organisms have a predilection for isolating themselves in specific sites in the body. This localization preference is probably an environmental phenomenon rather than an inherent or developed feature of the microorganisms.

The production of toxins by microorganisms and their dissemination by vascular channels are also recognized occurrences. One of the most dramatic examples is in scarlet fever, the remarkable cutaneous features of the disease being due to the erythrogenic toxin liberated by the infecting strep- tococci.

Rheumatic fever is an example of an important disease, which probably develops as a result of an altered reactivity or hypersensitization of the tissues to hemolytic streptococci. A high concen- tration of antibodies to antigens of the group of hemolytic streptococci is found in many patients with rheumatic fever. But the fact that microor- ganisms cannot be cultured from the blood or from any of the tissues involved in the disease indicates that this is not a direct bacterial infection. The importance of the oral cavity as a source for streptococci is obvious and will be discussed presently,

Oral Foci of Infection

A variety of situations exist in the oral cavity which are at least theoretical sources of infection and which may set up distant metastases. These include:

Infected periapical lesions such as the periapical granuloma, cysts, and abscesses.

Teeth with infected root canals.

Periodontal disease with special reference to tooth extraction or manipulation.

Bacteremia has been found to be closely relat- ed to the severity or degree of periodontal disease present after manipulation of the gingiva or, more commonly, after tooth extraction. As early as 1932, Richards had demonstrated that simple massage of inflamed gingiva resulted in a transitory bacteremia in 3-17 patients. Okell and Elliott reported that a transitory bacteremia developed in 75 per cent of a group of 40 patients who had severe periodontal disease after tooth extraction, but only in 34 per cent of 38 patients with ‘no noticeable pyorrhea’. The organism usually recovered was Streptococcus viridans. In 110 cases of periodontal disease in this same study, 11 per cent of patients showed a bacteremia at the time of examination, regardless of the operative procedure. But no positive blood cultures were found in a group of 68 patients who had no obvious gingival disease.

The ‘rocking’ of teeth in their sockets by forceps before extraction has been shown by Elliott to favor bacteremia in patients who have periodontal disease. Thus 86 per cent of patients with severe periodontal disease had positive blood cultures under the foregoing conditions, while only 25 per cent of patients with no demonstrable gingival dis- ease showed a bacteremia. Fish and MacLean have shown that the ‘pumping’ action occurring during dental extraction may force microorganisms from the gingival crevice into the capillaries of the gin- giva as well as into the pulp of the tooth. In their study, two teeth were extracted after cauterization of the periodontal pockets, and two others were extracted without bacteriologic precautions. Organisms were readily cultured from the pulp and periodontal tissues of the untreated teeth, but not from those with cauterized pockets. Burket and Burn utilized a tracer microorganism, Serratia marcescens, to demonstrate the forcing of microor- ganisms into the blood stream by ‘rocking the teeth during extraction. This microorganism was cultured from the blood of 60 per cent of 37 patients who had a suspension of the bacteria painted on the gingival margin before extraction.

Lazansky, Robinson, and Rodofsky studied the occurrence of bacteremia in 221 operations in the oral cavity involving 125 patients. Transient strep- tococcal bacteremias were found in 22 cases, or 10 per cent of the operations. A positive blood culture was found in 16 cases, or 17 per cent of a group of 92 multiple extractions, but only once in 56 single extractions. It is of considerable interest that a pos- itive blood culture was found in five cases of a group of 72 patients receiving simple periodontal scalings.

Even oral prophylaxis may be followed by bacteremia, as was demonstrated by De Leo and his associates in a group of 39 children between 7 and 12 years of age. Of these patients, 5 per cent were found to have a preprophylaxis bacteremia, but 28 per cent had a postprophylaxis bacteremia. On the basis of these findings, they concluded that it was mandatory that, prior to dental prophylaxis, antibiotic premedication be employed for those children diagnosed as having rheumatic or con- genital heart disease, because of the possible seri- ous consequences of bacterial endocarditis.

A great many other excellent pertinent studies dealing with tooth extraction or manipulation and bacteremia have been reported, some of which are summarized in Table 11-1. The evidence over- whelmingly indicates that the extraction of teeth. and sometimes even more minor oral procedures. may produce a transient bacteremia. This bac teremia seldom persists for over 30 minutes in the majority of patients.