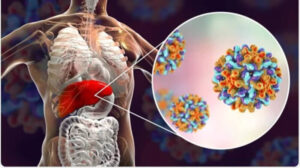

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver in which the tissue dies in patches. The condition can range from minor flu like symptoms to liver failure. It is caused by viruses or abuse of alcohol or drugs.

Acute Viral Hepatitis

At least six viruses appear to cause different forms of acute viral hepatitis:

Hepatitis A virus disappears after the infection. Once symptoms are gone, the disease cannot be spread to others (unlike hepatitis B and C). It does not lead to ongoing hepatitis or cirrhosis (liver damage).

Hepatitis B virus may become chronic or cause no symptoms in about 10% of the people infected.

Hepatitis C virus can develop into chronic hepatitis in about 75% of cases. Even at its first and sharpest stage, most cases of hepatitis C are not detectable using the usual clinical tests.

Hepatitis D virus can only develop when the hepatitis B virus is present. People who abuse drugs are at relatively high risk of developing this virus. It appears in very severe acute hepatitis B or an aggressive bout of chronic hepatitis B.

Hepatitis E causes widespread acute hepatitis seen in developing countries. It is often carried by contaminated water. It does not result in chronic hepatitis nor does it have a carrier state.

Hepatitis G appears to be passed from one person to another by contact with infected blood. It can cause some cases of chronic hepatitis.

Chronic Hepatitis

Hepatitis that lasts six months and ranges from acute hepatitis to cirrhosis is considered chronic. However, definitions vary, especially as more is learned about the many causes of the condition.

Symptoms

The symptoms of hepatitis can range from relatively mild to loss of life. Before symptoms of illness begin, a person may have a severe loss of appetite. A distaste for cigarettes is also an early sign. The patient may also experience a general feeling of being unwell, nausea, vomiting and often fever. Sometimes, especially in hepatitis B, hives and joint pain may occur.

After three to 10 days, the urine darkens, and a yellowish color develops in the skin. Some body fluids, such as bile, build up as a result of getting in the way of the work of the liver. The liver is usually larger than usual and tender, and in 15 to 20% of patients, the spleen is also larger than normal. Then symptoms begin to improve and the person feels better, even as the jaundice gets worse. Jaundice usually reaches its worst in one to two weeks. It then fades over the next two to four weeks.

Chronic Hepatitis

The signs of chronic hepatitis vary from person to person. About a third of the cases occur after the individual has had acute hepatitis. But most develop without that. In some people, especially those with chronic hepatitis C, there may be virtually no symptoms.

Commonly a person with chronic hepatitis may experience:

A vague sense of not being well

A loss of appetite

Tiredness

Low-grade fever

Discomfort in the upper part of the stomach area

Sometimes jaundice (a yellowish appearance to the skin because of disturbed liver function) will appear. Eventually, but sometimes not for years or decades, signs of liver disease will appear, including an enlarged spleen, a spider-like pattern of broken capillaries or fluid retention.

Causes and Risk Factors

Hepatitis A virus spreads mainly by contaminated food or water. The contamination may come from poor sanitation or infected blood and body fluids. Because a person may be infectious for two to six weeks before symptoms begin, epidemics can spread. This is especially the case in underdeveloped countries. This infection is most common in children and young adults.

Hepatitis B virus is often transmitted by contaminated blood or blood products. Infection can occur sexually, between a mother and an infant or by sharing needles. A person may carry the infection for six to 25 weeks before symptoms occur. Routine screening of donor blood has dramatically reduced the possibility of a hepatitis B infection after a transfusion. The risk is increased for patients in renal dialysis and oncology units and for hospital personnel in contact with blood.

Hepatitis C virus is most commonly acquired from contaminated blood, either through a transfusion or shared needles. It rarely is transmitted sexually or between a mother and an infant. A person can be infectious without having symptoms for three to 16 weeks. It plays a role in many cases of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and liver cancer. A small percentage of people who appear to be healthy carry the hepatitis C virus and have undetectable chronic hepatitis or even cirrhosis. About one in four people with alcoholic liver disease also carry the hepatitis C virus.

Hepatitis E virus is similar to hepatitis A in how it causes epidemics in poorer areas.

Hepatitis B and C viruses are usually responsible for chronic hepatitis. The B virus causes five to 10 percent of the cases and the C virus 75 to 80 percent. Hepatitis A or E viruses do not tend to cause chronic hepatitis. Why infection by some hepatitis viruses causes a chronic condition is not fully understood. Certain types of drugs or possibly genetically determined defects of metabolism may also cause it.

Many cases occur spontaneously and without a cause that can be identified. Wilson’s disease, a rare disorder that appears in children and young adults, may appear as chronic hepatitis. There are signs that the immune system may be involved in the process of liver damage, but this is not fully understood yet.

Diagnosis

In its early stages, hepatitis is hard to distinguish from a variety of flu-like illnesses. A doctor will do an examination and take the patient’s medical history. The doctor will also conduct tests to rule out tumors or blockages that may be outside the liver. A blood test may be done to help identify which virus is involved. In some cases where there are complications, difficulty reaching a diagnosis or unusual symptoms, a sample of liver tissue (biopsy) may be taken for analysis.

It is important to identify whether the condition is alcoholic liver disease, a flare up of acute viral hepatitis or cirrhosis.

Usually a sample of liver tissue is examined under the microscope to find out. A doctor will look for patches of dead tissue, signs of inflammation and the presence of fiber-like tissue. The fewer of these signs that are found, the better the outlook for the patient.

Treatment

In most cases, no special treatment is required, and people with hepatitis generally get well in four to eight weeks. Persons with hepatitis will have an up-and-down recovery and may have effects for several months or years. Appetite usually returns after the first several days, and patients need not be confined to bed. Most patients may safely return to work after jaundice goes away. Hepatitis A has the best chance for recovery.

Persons with hepatitis B, especially the elderly or those who have had a blood transfusion, have a lesser chance for recovery and have a higher risk of developing chronic hepatitis. About five to 10 percent develop chronic hepatitis. By contrast, 75 to 80 percent of all people with hepatitis C will develop chronic hepatitis, even when their first infection seems mild. Chronic hepatitis has a higher risk of developing cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Personal hygiene helps to prevent spread of hepatitis A. Blood of patients with acute hepatitis must be handled with care because it is infectious. The stool of patients with hepatitis A should also be considered infectious.

Ways to protect against the spread of hepatitis A include:

Injection of a hepatitis vaccine or of a special combination of antibodies called immune globulin

Travel precautions in areas where hepatitis is common. Peel and wash fresh fruits and vegetables, and do not eat raw or undercooked meat and fish. Use only bottled water.

Washing hands often. This is particularly important after using the bathroom, while preparing food or when changing diapers.

Vaccines exist against hepatitis A and B. Persons who are at a high risk of exposure to these viruses are advised to get the vaccination, including those traveling in third-world areas prone to hepatitis epidemics, healthcare workers and people who are on dialysis.

Treatment usually involves stopping the use of any drugs that may contribute to the condition and managing complications. If the condition is caused by an immune system problem, it is usually treated with corticosteroids, which tend to reduce swelling and irritation. However, people with hepatitis B and C should not be given corticosteroids because they make it easier for the viruses to replicate.

Treatment should always be supervised by a specialist. Often low doses of corticosteroids are needed for long periods of time. In some cases, the condition can progress even when it appears to be under control and managed.

Liver transplantation has not generally been considered as an option for end-stage liver disease caused by hepatitis B virus. Use of liver transplantation for treating advanced hepatitis C is more successful, although the infection tends to recur .