IMPACTED OR UNERUPTED TEETH

Bringing an impacted or unerupted tooth into the arch creates a set of special problems during alignment. The most frequent impaction is a maxillary canine or canines, but it is occasionally necessary to bring other unerupted teeth into the arch, and the same techniques apply for incisors, canines, and premolars. Impacted lower second molars pose a different problem and are discussed separately.

The problems in dealing with an unerupted tooth fall into three categories:

(1) surgical exposure,

(2) attachment to the tooth, and

(3) orthodontic mechanics to bring the tooth into the arch.

Surgical Exposure :-

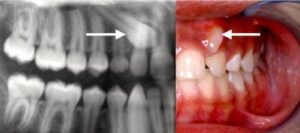

Before surgery to expose an unerupted tooth, it is obviously important to know with some precision where it is. This now is an indication for cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), using a unit with a small field of view (FOV) unless there is an indication for a large FOV (primarily, jaw asym- metry).” The older radiographic methods, a combination of the panoramic and an occlusal film (the vertical parallax method) or multiple periapical radiographs (the lateral cone shift method), require similar radiation exposure and provide much less information . With a CBCT image, often it is apparent that before an impacted canine can be pulled downward toward its position in the dental arch, it will be necessary to move it away from the roots of the central or lateral incisor-information that changes treatment plans and was not available with previous radiographic methods.

If an impacted canine is on the labial, removing tissue to expose the crown for bonding an attachment can be done conveniently with a diode laser.

A) The permanent canine was slow to erupt. Probing showed that exposure of 4 mm of the crown could be done without violating the biologic width of the attachment apparatus.

B) Immediately after crown exposure with a laser.

C) The tooth brought to the occlusal level with a superelastic wire, ready for placement of a bracket in ideal position

It is important for a tooth to erupt through the attached gingiva, not through alveolar mucosa, and this must be con- sidered when exposure of an unerupted tooth is planned. If the canine is labially positioned and probing shows that the crown is not covered with attached tissue, the crown can be exposed with a laser. If the unerupted tooth is more apically positioned in the mandibular arch or on the labial side of the maxillary alveolar process, a flap should be reflected from the crest of the alveolus and sutured so that attached gingiva has been transferred to the region where the crown is exposed. If this is not done and the tooth is brought through alveolar mucosa, it is quite likely that tissue will strip away from the crown, leaving an unsightly and periodontally compromised gingival margin. For a very high canine that is positioned labially, a tunnel method is an alternative to raising a flap. If the unerupted tooth is on the palatal side, similar problems with the heavy palatal mucosa are unlikely, and an open exposure can be used.

A spur on a lingual arch can be used in the mixed dentition either to maintain a correct midline when a primary canine is lost or to retain a corrected midline.

Occasionally, a tooth will obligingly erupt into its correct position after obstacles to eruption have been removed by surgical exposure, and delaying orthodontic traction to palatally impacted canines with incomplete roots is now recommended, but favorable spontaneous movement rarely occurs after root formation is complete. At that stage, even a tooth that is aimed in the right direction usually requires orthodontic force to bring it into position.

Method of Attachment :-

The best contemporary approach is to directly bond an attachment of some type to an exposed area of the crown. In many instances, a button or hook is better than a standard bracket because it is smaller. Then, if the tooth will be covered when the flap is replaced, a piece of fine gold chain is tied to the attachment, and before the flap is repositioned and sutured into place, the chain is positioned so that it extends into the mouth. The chain is much easier to tie to than a wire ligature. Before the availability of direct bonding, a pin was sometimes placed in a hole prepared in the crown of an unerupted tooth, and in special circumstances, this remains a possible alternative.

The least desirable way to obtain attachment is for the surgeon to place a wire ligature around the crown of the impacted tooth. This inevitably results in loss of periodontal attachment because bone that is destroyed when the wire is passed around the tooth does not regenerate when it is removed and increases the chance of ankylosis. Occasionally, no alternative is practical, but wire ligatures should be avoided whenever possible.

Mechanical Approaches for Aligning Unerupted Teeth :-

Orthodontic traction to move an unerupted tooth away from other permanent tooth roots, if necessary, and then toward the line of the arch should begin as soon as possible after surgery. Ideally, a fixed orthodontic appliance should already be in place before the unerupted tooth is exposed, so that orthodontic force can be applied immediately. If this is not practical, active orthodontic movement should begin no later than 2 or 3 weeks postsurgically.

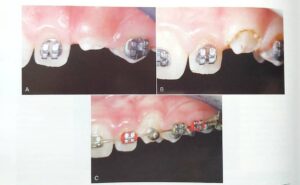

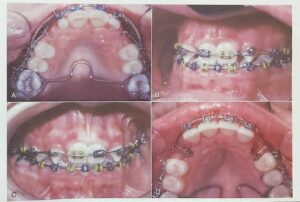

A) For this patient with palatally positioned bilateral impacted maxillary canines, a soldered lingual arch has been placed for better anchorage control; a heavy labial archwire is in place after space for the canines has been opened; and an auxiliary A-NiTi wire is tied to attachments (preferably, a segment of gold chain) that were bonded to the canines at the time they were exposed.

B) Progress in the same patient, with the A-NITI auxiliary now placed over a button that was bonded on the facial surface of the canine after it was brought down enough to allow this.

C) When the tooth has elongated enough, the button is replaced with a standard canine bracket and alignment is complete.

D) A vertical spring bent into a 14 mil steel archwire is an alternative approach to bring down an impacted canine. The spring is a loop of wire that faces downward before activation and is rotated 90 degrees for attachment to the impacted tooth or teeth. This method is effective but less efficient than using a superelastic auxiliary wire.

This means that for a labially impacted canine, orthodontic treatment to open space for the unerupted tooth and allow stabilization of the rest of the dental arch must begin well before the surgical exposure. In this instance, the goals of presurgical orthodontic treatment are to create enough space if it does not exist, as often is the case; and to align the other teeth so that a heavy stabilizing archwire (at least 18 steel, preferably a rectangular steel wire) can be in position at the time of surgery. This allows postsurgical orthodontic treatment to start immediately. For a palatally impacted canine, open exposure often leads to downward drift, so immediate active treatment can be deferred for many of these patients.

As we have noted previously, an unerupted tooth is an extreme example of an asymmetric alignment problem, with one tooth far from the line of occlusion. An auxiliary NiTi wire, overlaid on the stabilizing arch in the same way as recommended for other asymmetric alignment situations, is the most efficient way to bring an impacted tooth into position. The numerous alternatives include a special alignment spring, either soldered to a heavy base archwire or bent into a light archwire, or a cantilever spring from the auxiliary tube on the first molar.

Another possibility, magnetic force to initiate movement of an unerupted tooth, is especially attractive for a patient with other missing teeth in the maxillary arch because no mechanical connection is required. The technique involves bonding a small magnet to the unerupted maxillary tooth and placing a larger magnet in attraction within a palate- covering removable appliance. Unfortunately, success depends entirely on the patient’s cooperation in wearing the removable appliance with the intraoral magnet all the time.

Ankylosis of an unerupted tooth is always a potential problem. If an area of fusion to the adjacent bone develops, orthodontic movement of the unerupted tooth becomes impossible, and displacement of the anchor teeth will occur. Occasionally, an unerupted tooth will start to move and then will become ankylosed, apparently held by only a small area of fusion. It can sometimes be freed to continue movement by anesthetizing the area and lightly luxating the tooth, breaking the area of ankylosis. If this procedure is done, it is critically important to apply orthodontic force immediately after the luxation, since it is only a matter of time until the tooth reankyloses. Nevertheless, this approach can sometime allow a tooth to be brought into the arch that otherwise would have been impossible to move.

Unerupted or Impacted Lower Second Molars :-

Unlike impaction of most other teeth, which is an obvious problem from the beginning of treatment, impaction of lower second molars usually develops during orthodontic treatment. This occurs when the mesial marginal ridge of the second molar catches against the distal surface of the first molar or on the edge of a first molar band, so that the second molar progressively tips mesially instead of erupting. Moving the first molar posteriorly during the mixed dentition increases the chance that the second molar will become impacted. This possibility must be taken into account when procedures to increase mandibular arch length are employed. Many clinicians now delay or avoid banding of lower first molars because of this risk.

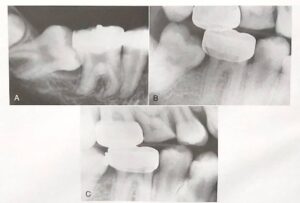

A) Radiographic view of an impacted mandibular second molar in a 16-year-old patient. Uprighting the tooth from this position requires surgical exposure of a portion of the facial surface of the crown and bonding an attachment (if possible, a tube) so that a spring can be used to tip it distally and bring it into the arch.

B) For a second molar that is caught on the edge of a first molar band, a simpler approach is uprighting achieved with a 20 mil brass wire tightened around the contact. Usually it is necessary to anesthetize the area to place a separator of this type.

C) Uprighting and distal movement obtained with the brass wire separator (same patient as B). A spring clip (one type is sold as the Arkansas de-impaction spring) can be used in the same way, but both brass wire and spring clips are effective only for minimal molar uprighting.

Correction of an impacted second molar requires tipping the tooth posteriorly and uprighting it. In most cases, if the mesial marginal ridge can be unlocked, the tooth will erupt on its own. When the second molar is not severely tipped, the simplest solution is to place a separator between the two teeth. For more severe problems, an attachment must be bonded to the second molar. An auxiliary spring often is useful to bring both upper and lower second molars into alignment when they erupt late in orthodontic treatment. The easiest way to do this is to use a segment of NiTi wire from the auxiliary tube on the first molar to the tube on the second molar. A rectangular wire, usually 16 x 22 M-NiTi, is preferred. This provides a light force to align the second molars while a heavier and more rigid wire remains in place anteriorly, which is much better than going back to a light round wire for the entire arch just to align the second molars.

When a second molar is banded or bonded relatively late in treatment, often it is desirable to align it with a flexible wire while retaining a heavier archwire in the remainder of the arch.

A) Repositioning a maxillary second molar, using a straight segment of rectangular A-NiTi wire that fits into the auxiliary tube on the first molar and the tube for the main archwire on the second molar.

B) Repositioning a mandibular second molar, using a segment of steel wire with a loop that extends from the auxiliary tube on the first molar. In both arches, after the repositioning, a continuous archwire can extend to the second molar.

Another possibility in adolescents is surgical uprighting of the impacted second molar, taking advantage of the space that is created when the third molar is extracted. In carefully selected cases, this can work quite nicely. Vitality of the second molar is retained because it essentially is rotated around the root apex, and the defect on the mesial of the uprighted tooth fills in with bone in the same way that it does when orthodontic uprighting is done. The outcome is best when some vertical jaw growth remains so that the uprighted tooth does not remain elongated relative to the first molar.