A periodontal flap is a section of gingiva and/or mucosa surgically separated from the underlying tissues to provide visibility of and access to the bone and root surface. The flap also allows the gingiva to be displaced to a different location in patients with mucogingival involvement.

CLASSIFICATION OF FLAPS :

Periodontal flaps can be classified based on the following:

▪︎Bone exposure after flap reflection

▪︎Placement of the flap after surgery

▪︎ Management of the papilla

Based on bone exposure after reflection :

The flaps are classified as either full-thickness (mucoperiosteal) or partial-thickness (mucosal) flaps .

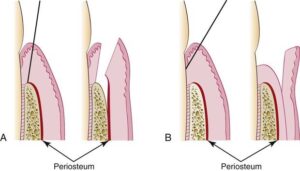

In full-thickness flaps, all the soft tissue, including the periosteum, is reflected to expose the underlying bone. This complete exposure of, and access to, the underlying bone is indicated when resective osseous surgery is contemplated.

The partial-thickness flap includes only the epithelium and a layer of the underlying connective tissue. The bone remains covered by a layer of connective tissue, including the periosteum. This type of flap is also called the split- thickness flap. The partial-thickness flap is indicated when the flap is to be positioned apically or when the operator does not want to expose bone.

Conflicting data surround the advisability of uncover- ing the bone when this is not actually needed. When bone is stripped of its periosteum, a loss of marginal bone occurs, and this loss is prevented when the periosteum is left on the bone. Although usually not clinically significant, the differences may be significant in some cases . The partial-thickness flap may be necessary when the crestal bone margin is thin and is ex- posed with an apically placed flap, or when dehiscences or fenestrations are present. The periosteum left on the bone may also be used for suturing the flap when it is displaced apically.

Based on flap placement after surgery :

Flaps are classified as (1) nondisplaced flaps, when the flap is re- turned and sutured in its original position, or (2) displaced flaps, which are placed apically, coronally, or laterally to their original position. Both full-thickness and partial- thickness flaps can be displaced, but to do so, the attached gingiva must be totally separated from the underlying bone, thereby enabling the unattached portion of the gingiva to be movable. However, palatal flaps cannot be displaced because of the absence of unattached gingiva.

Apically displaced flaps have the important advantage of preserving the outer portion of the pocket wall and transforming it into attached gingiva. Therefore these flaps accomplish the double objective of eliminating the pocket and increasing the width of the attached gingiva.

Based on management of the papilla :

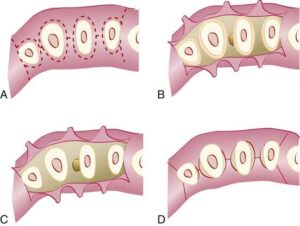

Flaps can be conventional or papilla preservation flaps. In the conventional flap the interdental papilla is split beneath the contact point of the two approximating teeth to allow reflection of buccal and lingual flaps. The incision is usually scalloped to maintain gingival morphology with as much papilla as possible. The conventional flap is used

(1) when the interdental spaces are too narrow, thereby precluding the possibility of preserving the papilla, and

(2) when the flap is to be displaced.

Conventional flaps include the modified Widman flap, the undisplaced flap, the apically displaced flap, and the flap for reconstructive procedures.

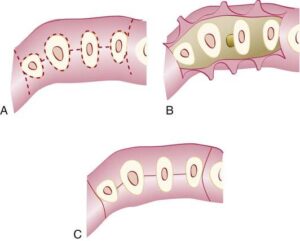

The papilla preservation flap incorporates the entire papilla in one of the flaps by means of crevicular inter- dental incisions to sever the connective tissue attach- ment and a horizontal incision at the base of the papilla, leaving it connected to one of the flaps.

FLAP DESIGN :

The design of the flap is dictated by the surgical judgment of the operator and may depend on the objectives of the procedure. The necessary degree of access to the underlying bone and root surfaces and the final position of the flap must be considered in designing the flap. Preservation of good blood supply to the flap is an important consideration.

Two basic flap designs are used. Depending on how the interdental papilla is dealt with, flaps can either split the papilla (conventional flap) or preserve it (papilla preservation flap).

In the conventional flap procedure, the incisions for the facial and the lingual or palatal flap reach the tip of the interdental papilla or its vicinity, thereby splitting the papilla into a facial half and a lingual or palatal half .

The entire surgical procedure should be planned in every detail before the intervention is begun. This should include the type of flap, exact location and type of inci- sions, management of the underlying bone, and final closure of the flap and sutures. Although some details may be modified during the actual performance of the procedure, detailed planning allows for a better clinical result.

INCISIONS :

Periodontal flaps use horizontal and vertical incisions.

Horizontal Incisions :

Horizontal incisions are directed along the margin of the gingiva in a mesial or a distal direction. Two types of horizontal incisions have been recommended: the internal bevel incision, which starts at a distance from the gingival margin and is aimed at the bone crest, and the crevicular incision, which starts at the bottom of the pocket and is directed to the bone margin. In addition, the interdental incision is performed after the flap is elevated.

The internal bevel incision is basic to most periodontal flap procedures. It is the incision from which the flap is reflected to expose the underlying bone and root. The internal bevel incision accomplishes three important objectives:

(1) it removes the pocket lining;

(2) it con- serves the relatively uninvolved outer surface of the gingiva, which, if apically positioned, becomes attached gingiva; and

(3) it produces a sharp, thin flap margin for adaptation to the bone-tooth junction. This incision has also been termed the first incision because it is the initial incision in the reflection of a periodontal flap, and the reverse bevel incision because its bevel is in reverse direction from that of the gingivectomy incision. The #11 or #15 surgical scalpel is used most often to make this incision. That portion of the gingiva left around the tooth contains the epithelium of the pocket lining and the adjacent granulomatous tissue. It is discarded after the crevicular (second) and interdental (third) incisions are performed .

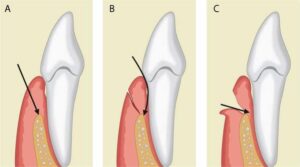

The internal bevel incision starts from a designated area on the gingiva and is directed to an area at or near the crest of the bone . The starting point on the gingiva is determined by whether the flap is apically displaced or not displaced .

The crevicular incision, also termed the second incision, is made from the base of the pocket to the crest of the bone . This incision, together with the initial reverse bevel incision, forms a V-shaped wedge ending at or near the crest of bone; this wedge of tissue contains most of the inflamed and granulomatous areas that constitute the lateral wall of the pocket, as well as the junctional epithelium and the connective tissue fibers that still persist between the bottom of the pocket and the crest of the bone. The incision is carried around the entire tooth. The beak-shaped #12D blade is usually used for this incision.

A periosteal elevator is inserted into the initial internal bevel incision, and the flap is separated from the bone. The most apical end of the internal bevel incision is more exposed and visible. With this access, the surgeon is able to make the third incision, or interdental incision, to separate the collar of gingiva that is left around the tooth. The Orban knife is usually used for this incision. The incision is made not only around the facial and lingual radicular area but also interdentally, connecting the facial and lingual segments, to free the gingiva completely around the tooth .

These three incisions allow the removal of the gingiva around the tooth (ie., the pocket epithelium and the adjacent granulomatous tissue). A curette or a large scaler (U15/30) can be used for this purpose. After removal of the large pieces of tissue, the remaining connective tissue in the osseous lesion should be carefully curetted so that the entire root and the bone surface adjacent to the teeth can be observed. Flaps can be reflected using only the horizontal incision if sufficient access can be obtained in this way and if apical, lateral, or coronal displacement of the

flap is not anticipated. If no vertical incisions are made, the flap is called an envelope flap.

Vertical Incisions :

Vertical or oblique releasing incisions can be used on one or both ends of the horizontal incision, depending on the design and purpose of the flap. Vertical incisions at both ends are necessary if the flap is to be apically displaced. Vertical incisions must extend beyond the mucogingival line, reaching the alveolar mucosa, to allow for the release of the flap to be displaced .

In general, vertical incisions in the lingual and palatal areas are avoided. Facial vertical incisions should not be made in the center of an interdental papilla or over the radicular surface of a tooth. Incisions should be made at the line angles of a tooth either to include the papilla in the flap or to avoid it completely . The vertical incision should also be designed so as to avoid short flaps (mesiodistal) with long, apically directed horizontal incisions because these could jeopardize the blood supply to the flap.

Several investigators proposed the interdental denudation procedure, which consists of horizontal, internal bevel, nonscalloped incisions to remove the gingival papillae and denude the interdental space. This technique completely eliminates the inflamed interdental areas, which heal by secondary intention, and results in excellent gingival contour. It is contraindicated when bone grafts are used.

ELEVATION OF THE FLAP :

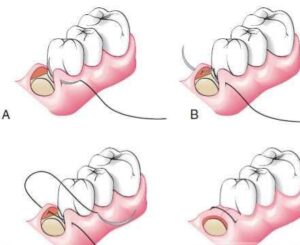

When a full-thickness flap is desired, reflection of the flap is accomplished by blunt dissection. A periosteal elevator is used to separate the mucoperiosteum from the bone by moving it mesially, distally, and apically until the desired reflection is accomplished .

Sharp dissection is necessary to reflect a partial-thickness flap. A surgical scalpel (#11 or #15) is used .

A combination of full-thickness and partial-thickness flaps often may be indicated to obtain the advantages of both. The flap is started as a full-thickness procedure, then a partial-thickness flap is made at the apical portion. In this way the coronal portion of the bone, which may be subject to osseous remodeling, is exposed while the remaining bone remains protected by its periosteum.

SUTURING TECHNIQUES :

After all the necessary procedures are completed, the area is reexamined and cleansed, and the flap is placed in the desired position, where it should remain without tension. It is convenient to keep it in place with light pressure using a piece of gauze so that a blood clot can form. The purpose of suturing is to maintain the flap in the desired position until healing has progressed to the point where sutures are no longer needed.

There are many types of sutures, suture needles, and materials. Suture materials may be either nonresorbable or resorbable, and they may be further categorized as braided or monofilament . The resorbable sutures have gained popularity because they enhance patient comfort and eliminate suture removal appointments. The monofilament type of suture alleviates the “wicking effect” of braided sutures that may allow bacteria from the oral cavity to be drawn through the suture to the deeper areas of the wound.

The braided silk suture was the most common non- resorbable suture used in the past because of its ease of use and low cost. The expanded polytetrafluoroethylene synthetic monofilament is an excellent nonresorbable suture widely used today.

The most common resorbable sutures are the natural, plain gut and the chromic gut. Both are monofilaments and are processed from purified collagen of either sheep or cattle intestines. The chromic suture is a plain gut suture processed with chromic salts to make it resistant to enzymatic resorption, thereby increasing the resorption time. The synthetic resorbable sutures are also often used.